Tourism - Access to the Lake

Utopias and the Wörther See

„A rose is a rose is a rose“ (1) „Du bist die Rose vom Wörthersee“ (2)

Semantic Reloading of a Post-Tourism Region – Utopias and the Wörthersee (3)

The Wörthersee in the south of Austria experienced its first heyday starting in the middle of the 19th century. In 1863 it became part of the rail network, evolving into a new holiday destination for wealthy inhabitants of the Danube Monarchy. As a result, a large amount of building work began around Carinthia’s largest and warmest lake; soon the architecture of the Wörthersee was shaped by villas, boat houses and country homes. The sale of lakeside plots and agricultural estates began after the First World War. Without any sort of prior planning, waterside plots were built on and sealed off. The biggest growth period took place between 1923 and 1934 and after 1945, with architect and planner, Rudolf Wurzer, outlining clear regional planning aims for Carinthia in his article “Über die bauliche Sanierung und Erweiterung der Seekurorte" (4) (“On the structural redevelopment and enlargement of lakeside health resorts”) . He highlighted the importance of separating health resorts, housing and agriculture and of developing planning associations based in the local town.

Nowadays, tourism at the Wörthersee has passed its zenith and is, in some lakeside areas, no longer of economic relevance. When it lost its importance as a holiday destination, what was previously a rural area became increasingly urbanised. At the same time the pattern of use began to change, tourism complexes and free plots of land becoming private holiday homes. However, no new industry came to replace that of tourism after 1945, with the situation being made more difficult by Carinthia’s economic and political legacy.

It is time to reimagine the potential of this area, particularly bearing in mind the region’s lack of a sustainable, comprehensive plan for the future, something that plays a decisive role in positive development. Ideas must be collected in order to initiate discussions and develop a new Wörthersee not dependent on tourism, or even simply to begin this process. Utopias – both positive and negative – are particularly suitable for this purpose. Different scenarios, spatial settlements and ways to new uses form links to real developmental possibilities – however absurd, exaggerated and polemic they might seem. Without a sense of direction or planning, who knows where the out-of-control growth and purchasing of the countryside will lead. The typical clichés of the region have been used up – the bad ones as well as the good. How can we break away from the area’s one-dimensional, stylised, glorified image? The following ideas aim to do just that.

Sport Utopia: The Wörthersee of the Bums (5)

Bums put their sport before anything else. To make this possible they live in cheap areas and only have occasional work. They value the sort of terrain and well-developed sport infrastructures that surround the Wörthersee. Furthermore, the extreme sport competitions that have taken place over the past few years such as the Ironman, the Wörthersee Ultratrailrun, the Swimming Marathon and the Klagenfurt Cycle Marathon attract the world’s most renowned sportspeople. An increasing number of tourism complexes reorient themselves to adapt to the new situation, with training centres gaining customers from all over the world. The local population is also motivated to take part in more sport. As the sport events and sport infrastructure create many job opportunities in the area, an increasing number of sport enthusiasts move to the Wörthersee. This results in an increase of creative potential: new sports and sports labels develop, sport becomes part of the culture and a pub, music and club scene develops.

Urban Utopia: The Wörthercity

A regional reform makes the Wörthersee city possible, with all the lakeshore communities fusing together. This spatial vision is a far cry from the image of a romantic Wörthersee – the space is urbanised, with a narrow city having developed along the parameter of the lake. The fundamental ideas behind the plan were published by Rudolf Wurzer in the 70s in a design for the central region of Carinthia. (6) The Wörthercity is, however, far more built up than in Wurzer’s suggestion, with the infrastructure spread around the lake. The area is transformed into a high quality garden city with the lake functioning as a central park. There are almost no private motorboats but, instead, electric boats operating as public ferries and taxis. Business parks are built along the motorway. Plots of land situated by the lake are gradually developed and the existing main streets undergo a gentrification process. Yet those aspects that make the area unique are not lost during the urbanisation process – in contrast, they become an important part of the local area.

Wörthersee-Resort

Selling free plots of land to wealthy families for housing is seen to be more sustainable and ecological for the Wörthersee development area than handing them over to tourists. This connects a sophisticated, wealthy community of residents to the area around the Wörthersee for generations, in turn increasing the value of the remaining infrastructure. These properties require both security and social freedom and are therefore placed next to each other with generous green spaces in between. This also makes it possible to rejuvenate architectural eyesores. Properties are enclosed, with the entrance to the properties, and therefore also to the lake, being managed by a security company, preventing unwelcome guests. Around Velden, a millionaire district develops, with an equally exclusive infrastructure. This area, with restricted entrance, forms a contrast to the otherwise introverted properties with their high fences blocking the view to the lake.

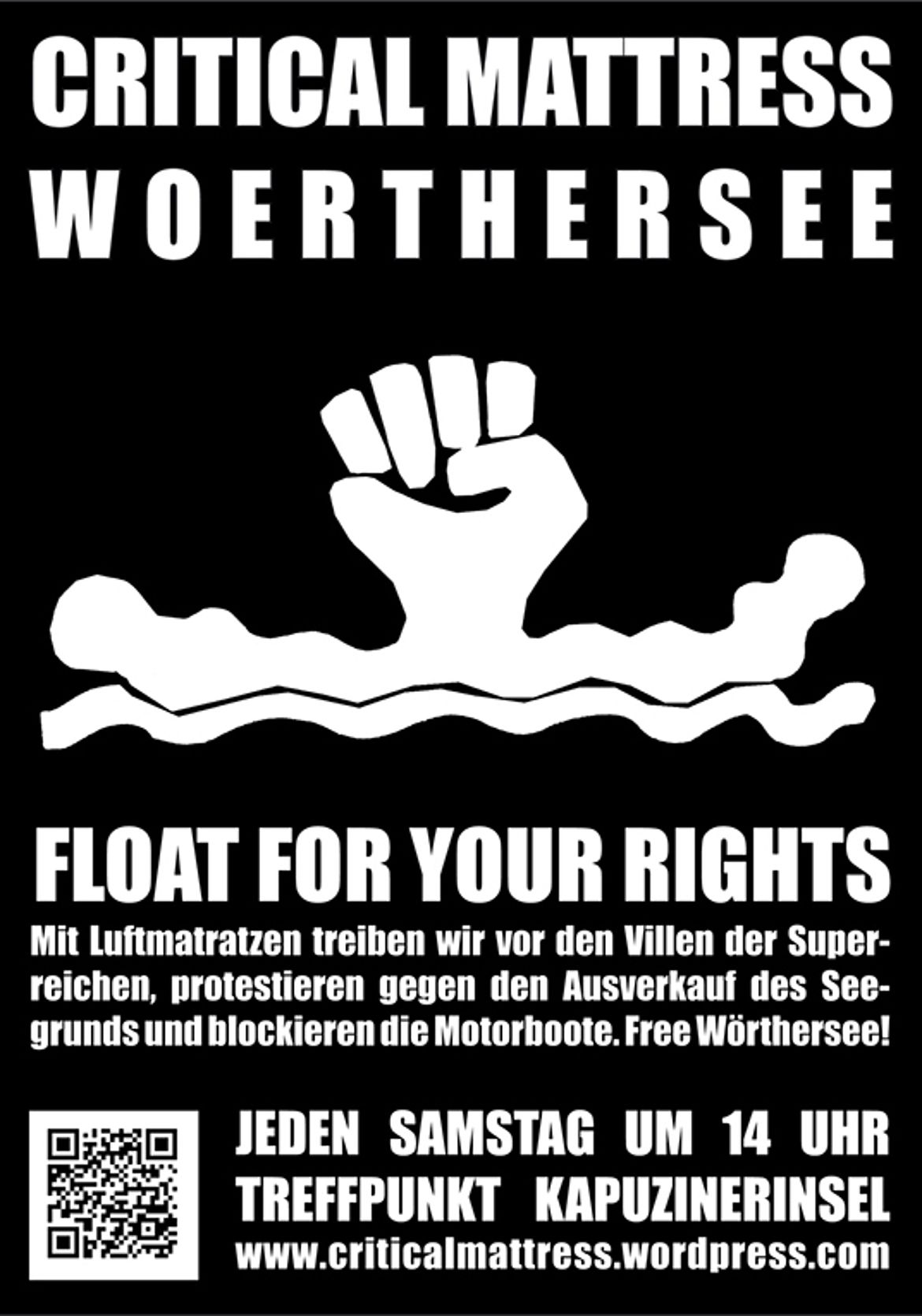

Radical Utopia: A Lake for All!

Public anger is directed at the super-rich snapping up properties at the Wörthersee, acquiring the remaining free lakeside areas. The privatisation of the bathing area was the last straw. There are now only a very few meters of publically accessible lakeside available and even the last few plots in the second row will soon be inaccessible to the general public. Radical policies have often found support in Carinthia. The threat of an alliance between the Freedom Party of Austria and the Alliance for the Future of Austria is still breathing down the Carinthians’ necks and has now caused a very different type of movement to take roots: there are plans to give the lake back to the people. (...)

1) Gertrude Stein in the poem Sacred Emily 1913 and in Geography and Plays, 1922.

2) “You are the rose from Wörthersee” – film music by Hans Lang, 1952.

3) This text is an extract from the research project “Semantical Reloading der Wörthersee-Region oder Post-Tourismus: neue Chancen für eine teilweise abgetakelte Tourismusregion” (“Semantical Reloading of the Wörthersee Region or Post-Tourism: new chances for a partially rundown tourist region”); supported by the Margarethe-Schütte-Lihotzky-project-scolarship of the Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture, Vienna.

4) Rudolf Wurzer, “Die Entwicklung, Sanierung und Neuordnung der Seekurorte Kärntens”, in: Der Aufbau, Wien 1949, p. 357–406.

5) Bum can be used to describe not only layabouts but also sports fanatics. Examples include ski-bums or bike-bums. These people usually live in North America and do nothing other than practice their sport, taking it to an extreme level.

6) Rudolf Wurzer, “Zentralraum Kärnten, zentrale Orte und regionale Siedlungsstruktur um 1990”, in: Amt der Kärntner Landesregierung (publisher), Raumordnung in Kärnten, Entwicklungsprogramm Kärntner Zentralraum, vol. 7, design, Klagenfurt 1974.

* This is a text extract of the research project (3) and was published in:

Re-Searching Utopia- When Imagination challenges Reality, TU Wien, Abteilung Wohnbau und Entwerfen – Cuno Brullmann (Hrsg.), Niggli Verlag, November 2014